Great Migration, Pt. 2: Systematic Oppression Back Then and Now

by Diamond Afeni

“It occurred to me that no matter where I lived, geography could not save me.”― Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns

Systematic oppression, at its core, is defined as the ability to oppress people based on their identity or societal standing. That means: If you’re rich, you’re treated well; if you’re poor, no one cares. Simply put, Black people, specifically descendants of those enslaved, have been systematically oppressed since we’ve been here.

In Part 1, we learned that Black people migrated north to provide better lives for their families, after escaping the south. Northern cities typically provided better education for Black people (although limited in resources), which is another reason some decided to migrate. For context, many Black people in southern states didn’t move past a 6th grade education. I can personally attest to this, as my great-grandfather (still living) who was born in 1937, dropped out of school in exactly 6th grade to work. That is an example of systematic oppression. I can still remember him taking me with him to pay bills so that I could read for him (so that the people wouldn’t get over on him).

Nevertheless, education was only a small factor of systematic oppression. While our people dealt with ongoing realities of being Black, building wealth didn’t come easy for many. The housing market played a role in this, back then and now.

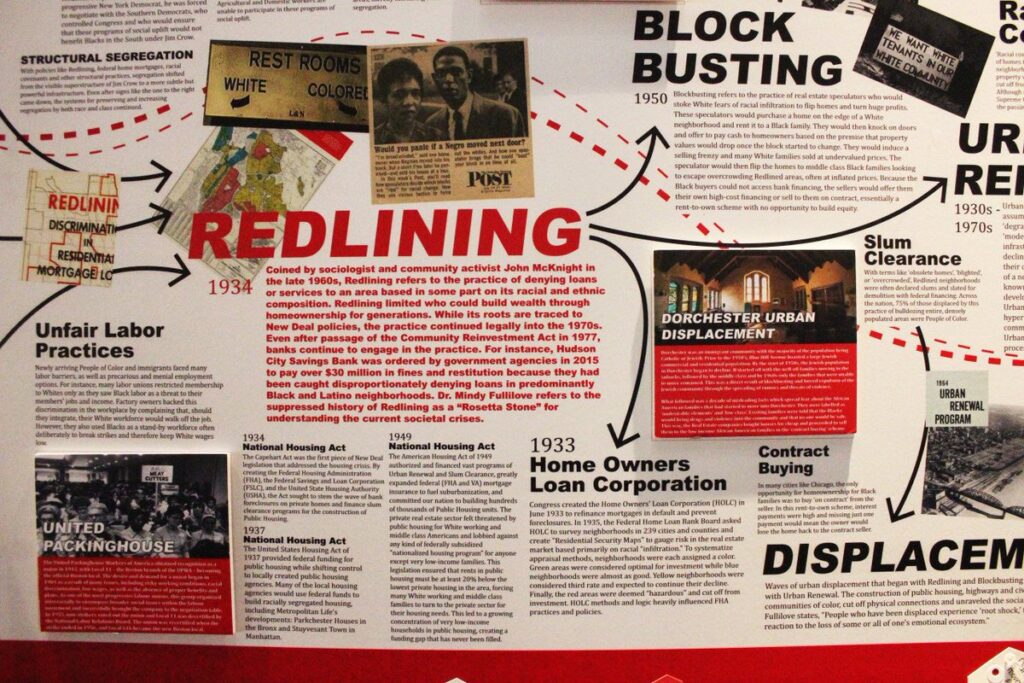

Redlining and How It Effected Generational Wealth

Redlining is defined as “a discriminatory practice in which mortgage lenders restricted loans to certain communities.” Redlining ain’t a discriminatory practice. It’s simply racist and rooted in capitalism. The wellbeing of people ain’t a concern of capitalism; it’s only interested in getting more for less.

Let me break it down a little more…

The Great Depression happened during the years of The Great Migration. The stock market crashed, the economy went under, and many were left without jobs. There was a popular saying for Black workers back then: “last hired, first fired.” If one of our elders were telling this story, they’d probably say “now ain’t that sum’n?”

Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was president at the time, created the New Deal, which was a series of federal programs to help “all” citizens. The Federal Writer’s Project is an example of one of those programs. It was started in 1935, and one of the projects of this particular program was The Slave Narrative Collection. Teachers, writers, and librarians were paid to interview formerly enslaved people about their experiences during slavery. Those stories recorded for that particular collection actually inspired the start of Krak Teet.

Another program, the Home Owners Loan Corporation, for example, was created to assist citizens with financing their homes to prevent foreclosure.

But this didn’t include us.  The program was strategically created to keep Black people from owning homes, receiving assistance, and loans because banks and small lenders didn’t finance to those living in areas marked as “hazardous.” Most Black people lived in these areas. Mind you, segregation was still evident in the north, so Black people lived in the same neighborhoods, making it easier to target us. They even created maps to mark these neighborhoods.

The program was strategically created to keep Black people from owning homes, receiving assistance, and loans because banks and small lenders didn’t finance to those living in areas marked as “hazardous.” Most Black people lived in these areas. Mind you, segregation was still evident in the north, so Black people lived in the same neighborhoods, making it easier to target us. They even created maps to mark these neighborhoods.

This happened throughout the entire country. “With nearly 65% of its neighborhoods marked in red, Macon, Georgia was the most redlined city in the U.S.” (Investopedia) People within these communities were considered “too risky” to lend loans. In the 1930s, there were 10 cities mapped as being the most hazardous throughout the nation. Georgia had three: Macon, Columbus, and Augusta.

If systematic oppression needed a face…look at the resources (schools, homes, and wages) that are provided within these cities some 80+ years later. You don’t have to look far to notice that federal capitalism and corporations take over small impoverished communities to gentrify them. They forcibly move people out by ways of corporate threats (raising rent, taxes, increasing police, and refusing to provide better amenities).

These same hazardous living areas would be seen in cities such as Chicago from the 1960s until present day.

Chicago’s Contribution

While we know that slavery was illegal in northern states, existence of Black life in Illinois was less than 2% after slavery ended. Black people began migrating to Chicago after World World I, holding the largest numbers of the migration at that time (close to 100,000 throughout the years). Between 1940 and 1944, more than 60,000 Black people migrated to Chicago. By the early 70s (which is also when the migration began to end), Black people had made up a third of the city’s population.

Throughout the years of the migration, Black people were limited to an area in Chicago called “The Black Belt.” The Black Belt was a chain of neighborhoods on the South Side of Chicago, and it housed about 75% of the city’s Black folk. The Black Belt was a direct result of systematic oppression. White people refused to allow Black people in their neighborhoods, so they created restrictive and illegal practices to keep them out.

These practices included creating documents that stated that homeowners couldn’t rent or sell their homes to Black people. Ultimately, this led to overpopulation in these areas and investors began creating “kitchenettes” (small compartmentalized apartments). Although kitchenettes were common for all races, the conditions for Black people living in them were significantly worse compared to the white people’s.

Lorraine Hansberry’s play (which later became a book and movie), A Raisin in the Sun, was set in the 1950s on the South Side of Chicago and portrays this problem very well.

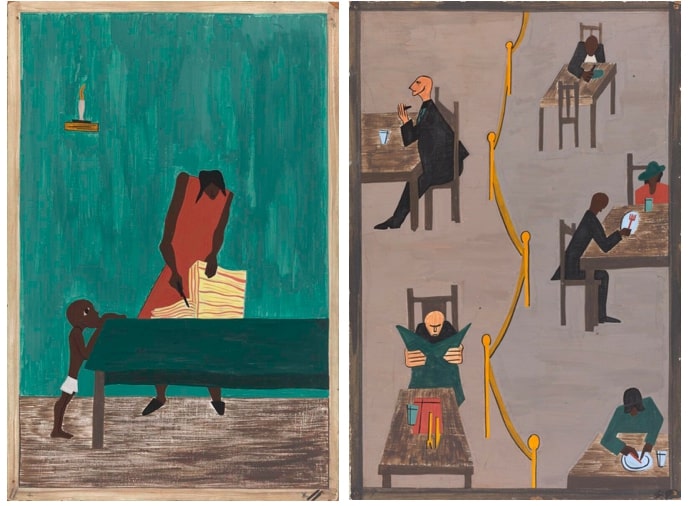

The picture above represents a visual of how many kitchenettes were structured. In the south, the concept of these are called “shotgun” houses or even shacks. All were/are symbols of poverty, usually within the hood/ghetto. Gentrification has a way of historically changing the meaning of things for profit tho.

Years later, restrictive practices would be ruled out as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, but this still didn’t stop discriminatory practices such as redlining. While many were allowed to now buy and rent homes, the monthly rates were significantly higher (although this was illegal). Black people signed contracts that had hidden stipulations. These stipulations gave landlords and lenders permission to remove Black people for anything, including complaining.

Why did we sign such horrible deals? The first batch of black folk to move North desperately needed somewhere to live. Once they found housing, more family would move up and live with them until they got on their feet. This often crowded an already overcrowded apartment, which led to desperation. When you’re desperate (and probably illiterate too), you’ll sign just about anything to improve your living conditions.

Black Cities and Systematic Oppression: Connecting the Dots

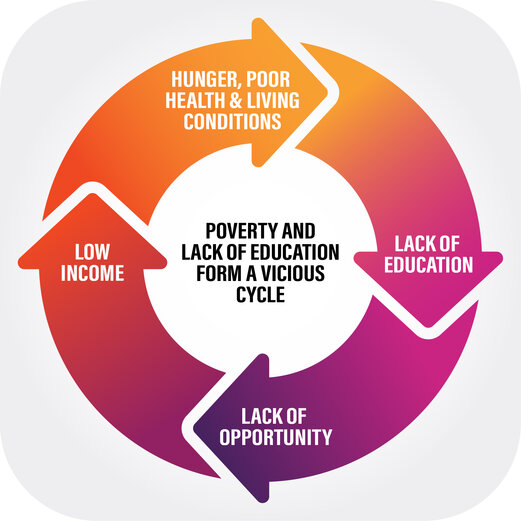

We’ve all heard the terminology “Black on Black crime,” but it’s simply a myth. The issue is proximity, which is why the practices created during The Great Migration still affect us. Those practices created overpopulated areas, which would lead to crimes committed by those within the same areas, in the 1960s and forward. Crimes most commonly committed in Black neighborhoods were/are gang-related, involving guns and drugs. While these things are commonly discussed by biased media, there are things that are forgotten.

- Poverty creates crime.

- Gangs were originally created to protect communities. This began to change with the rise of drugs that were placed in our communities in the late 70s. Crack.

- Crack was purposefully placed in our communities to divide and conquer. This drug would later lead to what’s called “the crack epidemic,” which contributed to mass poverty within our communities. This would then lead to the war on drugs and mass incarceration, which would further destroy homes and wealth accumulation.

- Marvin Gaye sang about this in “What’s Going On?” Tupac rapped about it in “Changes.” And Lauryn Hill sang about it in “Mystery of Iniquity.”

These details are important because they created (and still create) systematic oppression within our communities. The more oppressed you are, the more likely you are to be a “have-not.” Not having it is stressful and depressing, which leads to vices like drugs, alcohol, gambling, and violence. These vices create traumatic home environments, which, in turn, creates more financial burdens, mental health challenges, and other generational wounds.

It’s simply a ripple effect.

Up Next: Part 3 will discuss Gentrification and The New Migration: Back to the South. Make sure you’re subscribed to our newsletter, if you ain’t already.