Susie King Taylor Saved Savannah + Krak Teet

Susie was born August 6, 1848 in Liberty County, Georgia, which is 30-something miles from Savannah. She was the eldest of Hagar Ann Reed and Raymond Baker’s 9 children. Susie moved to Savannah when she was about 7 years old, which was still about 10 years before the Civil War ended and all black people were freed by law.

Her grandmother hooked Susie up with all kinds of people to secretly teach her how to read, do math on paper, and much more. The first teacher, an older black woman, she learned everything the woman knew. The second teacher, a white girl, got sent away to a convent. The third teacher, the white landlord’s son, got drafted into the Civil War. (He eventually switched to the Union’s side.)

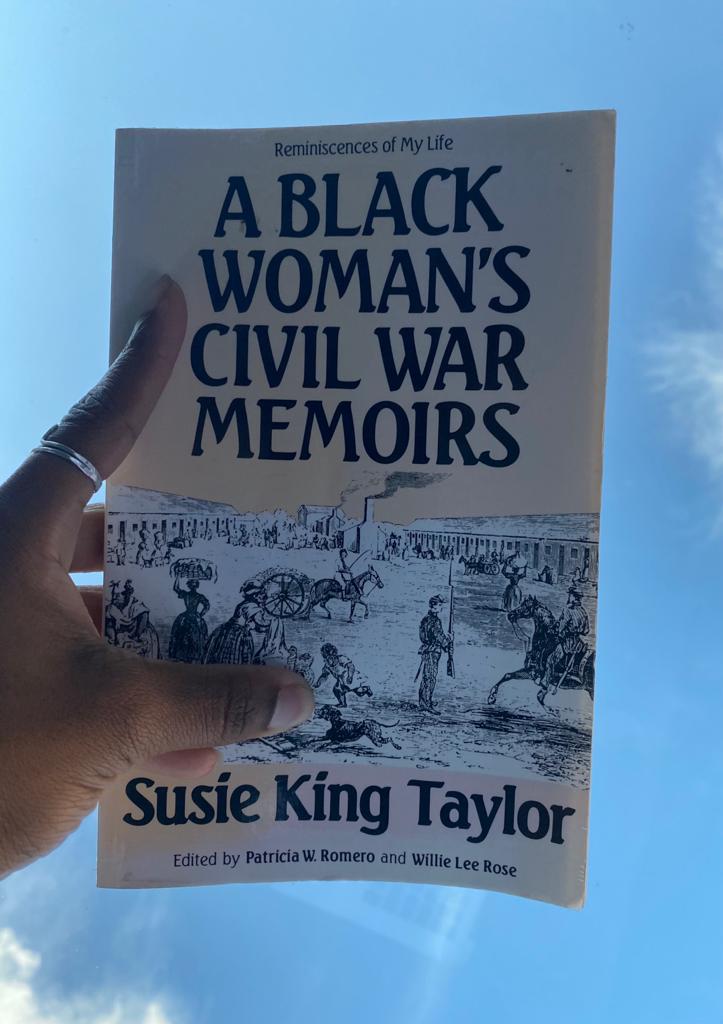

She’d write passes for her grandmother, which her grandmother would either use for herself or give to other black folk. Remember back then, whether you were enslaved or free, you needed a written pass from the court or the white person who owned you to show police or slave-catchers. In Susie’s autobiography, Reminiscences of My Life, she even shared what she used to write on the passes:

Savannah, GA., March 1st, 1860. Pass the bearer _________ from 9 to 10:30 P.M. -Valentine Grest

Her book taught me the importance of talking to your kids about what’s going on in the world–even if you feel like they wouldn’t understand. White folks in Savannah wanted black folk to be scared of the Yankees (the white men from the North). They’d tell ’em stuff like Yankees would replace their horses with black people. If black folk believed them, they’d likely end up fighting with the Confederates and against the Union, which meant they’d be fighting against their own emancipation. Susie’s grandma gave her the game though, so Susie looked forward to the Yankees marching into town.

How Susie King Taylor made history

On April 3, 1862, after the Union took Ft. Pulaski, Susie’s uncle took his family of seven and Susie to St. Catherine Island. From there, they were taken to St. Simon’s Island. One of the Union ship’s captains asked Susie for her name and if she could read and write. Then he made her prove it. The next part I love so much.

He said: “You seem to be so different from the other colored people who came from the same place you did.” Instead of taking that as a compliment, she said, “No! The only difference is, they were reared in the country and I in the city.”

From there, she started working with the Union Army. She sewed their clothes, cooked their meals, became their nurse, and taught black children and adults who had just gotten their freedom how to read and write. She soon attached herself to the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first black regiment in the US Army.

Susie King Taylor is known as the first black nurse of the Civil War. If your people were in the Civil War in this area, she might be the reason you here. Soldiers who had diseases like malaria, measles, cholera, and smallpox were often left to die, because it was so contagious and deadly. So these sick soldiers were quarantined and left to fend for themselves. She wrote in her book, “I was not in the least bit afraid of the small-pox. I had been vaccinated, and I drank sassafras tea constantly, which kept my blood purged and prevented me from contracting this dreaded scourge.”

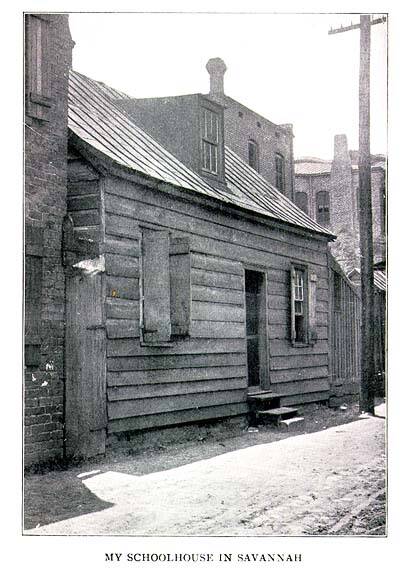

She’s the only woman to have published a book about her experiences during the Civil War. And after the war was over, she opened the first school in Savannah, Georgia for free black people. A lot of records say that her school “failed” once a public school opened in the city, but I think it served its purpose. Everything has a beginning and an ending. Reaching your ending don’t make you unsuccessful; it ran its course.

Around the same time her school closed, her husband died. She sent her son back home to her people in Liberty County ’til she got on her feet. That’s so relatable, reminding me how my mama left me with my grandma ’til she got out the Gulf War and on her feet. So many of us can relate to that. She started cleaning white folks’ houses, as many black women did then, to earn some money. When her employers moved to Boston in 1872, she went with ’em.

She remarried in Boston and nursed war vets for the Women’s Relief Corps, a national organization for female Civil War veterans. Then she became their guard, secretary, treasurer, then the president.

She died in 1912 at 64 years old in Boston. Savannah has a ferry and a school named after her.

How I learned about Susie

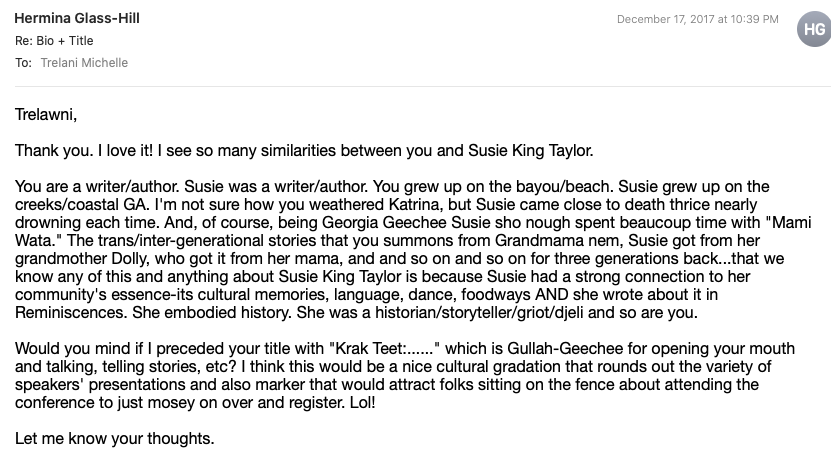

I “met” Susie King Taylor around 2016 when I got heavy into my research about Black Savannah backintheday. About a year later, Hermina Glass-Hill reached out to me to see if I’d speak at her Susie King Taylor Mami Wata Rising Conference. First off, Hermina is just phenomenal! An amazing historian, writer, protector of Mama Earth, and Executive Director for the Susie King Taylor Women’s Institute and Ecology Center in Midway, Georgia. She’s made it her mission to keep Susie’s life and legacy lifted.

Hermina pointed out how much I reminded her of Susie King Taylor. Here’s a snippet of the email:

I said yes for three reasons:

- I loved Hermina and her work.

- I loved Susie King Taylor.

- I loved Mami Wata (aka Yemaya, the African water spirit).

How Hermina and Susie King Taylor made way for Krak Teet

Before this book and movement was called Krak Teet, it was called We Speak Fuh We. For legal reasons, that wasn’t working no more and I needed a new name. I was juggling Krak Teet and two other names. When Hermina sent this email and asked if she could name my presentation Krak Teet, that sealed the deal for me.