More Black Folk Need to Know Phillis Wheatley

Written by: Breanna (@tenlibras) and Trelani Michelle

Phillis Wheatley remains relatively unknown, despite her major accomplishments. Named after the ship she arrived on from West Africa when she was 7 or 8 years old in 1761, Phillis was the first woman in America to publish a book. Not just the first black woman but the first woman altogether. She was also the first published African American poet.

Even with all of these accomplishments under her belt, she still is hidden in the shadows. When conversations about Black authors are brought up, her name is rarely ever said. Why is that?

Phillis Wheatley was born in Gambia in or around 1753. (I wish we knew what her parents named her.) When she arrived on the boat, she looked so weak and frail they were sure she wouldn’t survive much longer. Susanna Wheatley bought her with mere change, hoping to make her a “domestic” since she was deemed too ill for any rigorous labor. They taught her to read and write while she cleaned up around the house and did other common chores.

She learned English in just a year and immersed herself in literature. In her poems though, she acknowledged her privilege of being literate in English while also yearning for more education and exploration. She began writing poetry around 13 years of age, though none of it published until 1767. Her first public works were eulogies of well-known figures, gaining her exposure in New England (where she resided). Her first published poem, “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that Celebrated Divine, Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Whitefield,” was a tribute to George Whitfield, a popular minister at the time.

Many scholars believe she began writing at a much earlier age than that though. Her first collection of poems Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) was met with disbelief initially. She was about 18 years old around this time. A group of Boston’s most wealthy and well-connected white men called her to a meeting to “test” her. The governor and lieutenant governor of Massachusetts were among them, in addition to John Hancock and 15 others. They couldn’t believe that Phillis Wheatley, a black girl who not long ago just arrived to this country and learned English, could write an entire manuscript of poems.

Can you imagine how nerve-rattling that meeting had to be for her?

After the meeting, they wrote “a young Negro Girl, who was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa, and has ever since been, and now is, under the Disadvantage of serving as a Slave in a Family in this Town.”

Her book was published soon after this meeting, THEN her human traffickers (aka owners) freed her.

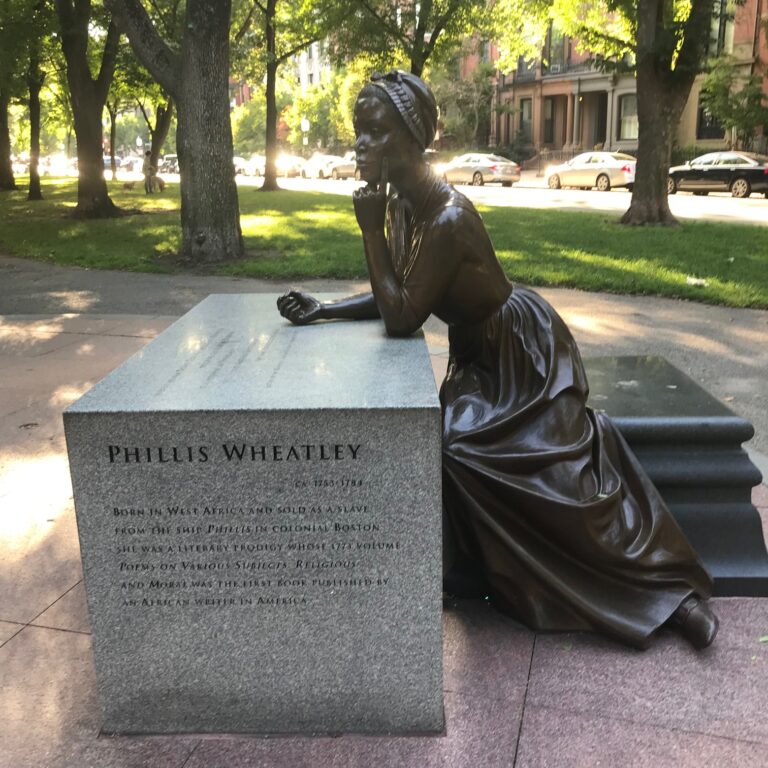

A monument of Phillis Wheatley in Boston

While she wrote about concepts like freedom, her poetry reminds me that she was raised and taught by white slave-owners. Textbooks try to romanticize it and say that they treated her as if she were their own child, but no sane person would enslave their own daughter. This is also a testament to why black students need black teachers. Here’s one of her shorter poems, called “On Being Brought from Africa to America”:

‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

Then again, maybe she was fooling all of us. Maybe she was writing what they wanted to read. Pulling some Booker T. Washington type shit and proving to white folk that we were capable of being peaceful and productive people, deserving of freedom. Who knows?

Nonetheless, Phillis Wheatley got respected reviews from well-known figures like Benjamin Franklin. She went beyond poetry and wrote protest letters as well, proving that she was not only creative but a critical thinker. She was aware of what was going on in the world, had a valid two cents as to what needed to be done about it, and wasn’t afraid to go straight to the top of the chain of command to speak her mind.

At 19 years old, she wrote to the King of England to discuss the unfair taxes that Britain was putting on America. He invited her to England where she impressed everybody there with her ability to not only speak English fluently but Latin and Greek as well. She also wrote a letter to George Washington to explain how much of a contradiction it was for America to be fighting for its freedom while slavery was still big and healthy here. She was about 22 around this time, and he also invited her to come talk with him further about liberty and justice.

For as many admirers as we shall have, there shall also be haters…

Thomas Jefferson was one of her biggest critics. He claimed that she lacked imagination and that all of her talent was essentially spun off of her obvious bible reading. He downplayed her talents. In his book, he wrote that her poetry was “below the dignity of criticism.” That’s hilariously ironic, though, because he found it necessary to write about it in his book.

Unfortunately, her story didn’t end well though. Against her close friends’ wishes, she married a free man from Boston named John Peters. He was good looking and often wore wigs and carried canes, not because he needed ‘em though; that was the style. He’s also said to have been a lawyer, barkeeper, grocer, writer, speaker, and more. If it’s true, that actually ain’t uncommon. Many men, black and white, worked multiple jobs to make ends meet back then. It’s also a possibility that it ain’t true though. Some sources referred to him as a conman.

Whatever the case, he was horrible with money. He owed money before they married and the debt multiplied during the marriage. It seems he nearly lived in the courthouse dealing with lawsuits. He spent many years on the run, trying to dodge imprisonment, and he spent more years in and out of jail for debt.

During one of his stints in jail, Phillis was pregnant with their third child. The previous two children died as infants. With her husband gone, she was left to fend for herself, so she didn’t have time to write anymore. All the while this is going on, the country was also at war with Britain. That caused a recession of sorts, hard times on nearly everyone.

She tried getting another book published, but it never happened. She found work as a wash woman in a boarding house then developed pneumonia and died–she and her newborn baby–on December 5th, 1784. She was only 31 years old.

Phillis Wheatley is so deserving of our attention. If for nothing else, she was the first woman to become a published author in this country. And during a time when most black folk weren’t going beyond the borders of the plantation they were held hostage on, Phillis was traveling abroad to meet with world leaders to discuss politics. Though she died tragically young, she did SO much in her three decades.

Thanks. the article about “Phillis Wheatley” enlightened my soul. I will hold on to it for future reference for my grandchildren. You will hear from me soon.

You’re so welcome.