Educating Indigenous Children Worked Better Than War

This article ain’t a thesis. It’s more like a journal entry to share some of my recent aha moments. And because this topic is so huge (it’s deep, y’all), I’m going to do my best to condense it.

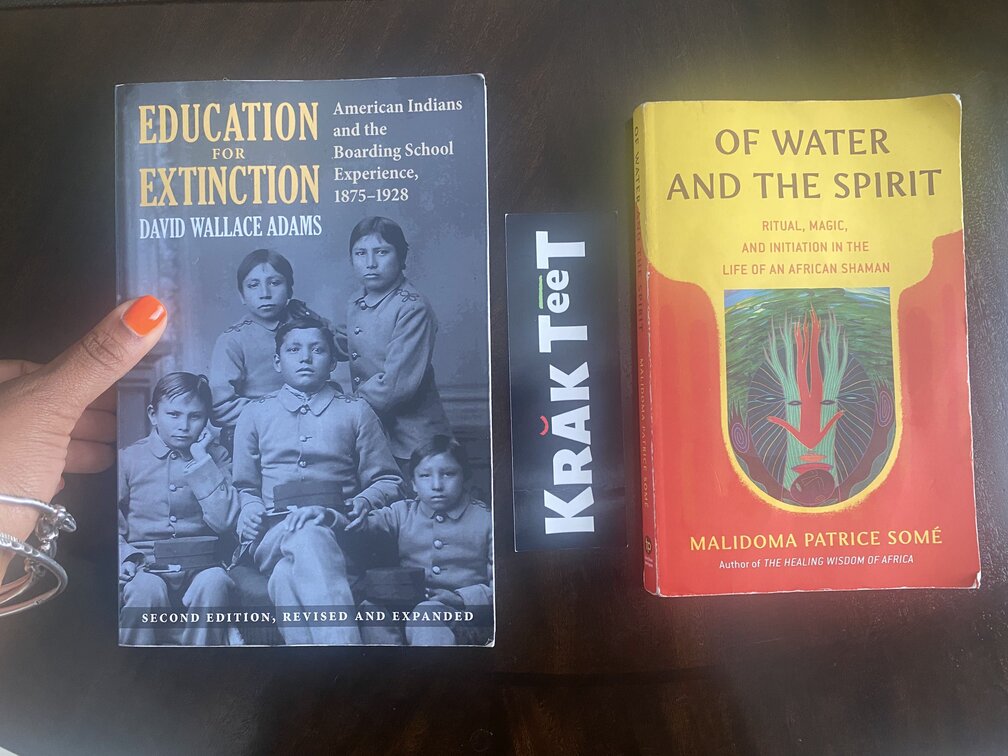

I started connecting the dots while reading Of Water and The Spirit by Malidoma Patrice Somé. The book is about his experience of being kidnapped and raised by Catholic priests in West Africa. He was four years old when he was kidnapped; it was 1956. You’d have to read the book for the details, but basically his father had already developed a relationship with the white missionaries. His grandfather couldn’t stand ’em though because White settlers had gone from asking for land to taking it. Snatching folks’ farms and homes from right up under ’em.

Dagara culture situated children to spend more time with their grandparents than their parents in their younger years. When Malidoma’s grandfather passed away, white missionaries took him. And kept him until he ran away at 19 years old. First he was taken a boarding school up on the hill, not far from home. Though traumatized, the land ain’t unfamiliar and there’s a Dagara brother who’s responsible for “breaking ’em in.”

Off top, the kids are taught French and English, and are punished for speaking their native language. History lessons are exclusively white. They’re forced to become Catholic. They had to dress like the white folks, not like their family back home (who they never get to see). And they get new names! Many of the boys ended up forgetting the name they born with.

Around high school age, they transfer to another school that’s farther away from home. Lessons are more advanced and the end goal is finally made clear: They won’t be kept forever. Around 21 years old, they’ll be released with the expectation of saving Africa. Religiously, yeah, but, more importantly, culturally. The purpose of the boarding school, we learn, is to ultimately get the students to do the work of the colonizer. To convince their own people that their way of life is backwards and that it’s in their best interest to live, speak, and pray like the white man.

The intention was to create a system of haves and have nots. In order to make that happen, you need laws, taxes, big businesses, and workers for those big businesses. Those workers can’t have so much free range though. The land needed to be parceled out. They need to be convinced that they don’t have enough, that they need more. Those who work in the big businesses will get more. Those who live, speak, and pray like the colonizer the most will have the luxuries that those still living in the old ways won’t (e.g., a big house, a car, fancy clothes, etc.).

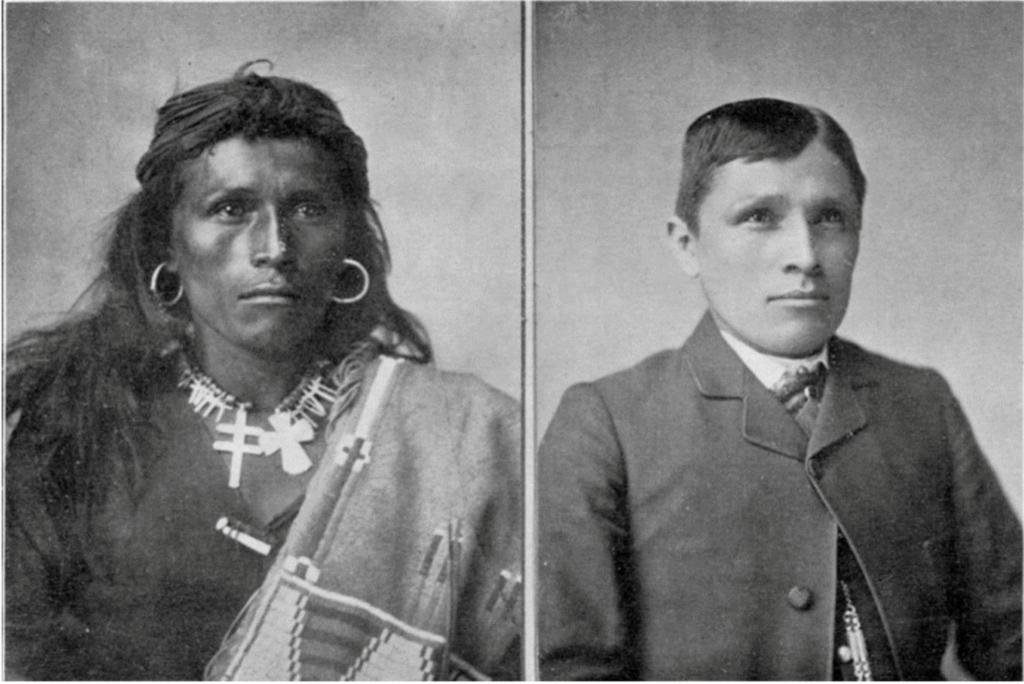

While reading about Malidoma’s story—especially the part about getting a new name and a new look in the boarding school—I thought about Hastiin To’Haali, a Navajo brother who was renamed Tom Torlino in a boarding school here in what we now call North America. Back when I taught high schoolers, I shared the before and after picture of Hastiin with my students during a lesson on respectability politics.

This was a big lightbulb moment! The same thing that happened in Africa happened right here in North America. We hear about indigenous nations being tricked out of their land and going to war. But we don’t hear that much about the education process and that was the biggest key! War is expensive! Education, however, ain’t nearly as costly.

After finishing Of Water and The Spirit, I wanted to learn more about boarding schools on this land. So I bought Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928. One of the first lines I highlighted said: “Commissioner of Indian Affairs Henry Price opined: ‘Savage and civilized life cannot live and prosper on the same ground. One of the two must die.’ Certainly, reformers hoped that Indians would choose assimilation over extinction.”

Another line I highlighted: “Merrill Gates, president of the Lake Mohonk Conference, declared in 1891 that ‘the time for fighting the Indian tribes is passed.’ What was needed now was an ‘army of Christian school-teachers.'”

Another: “It is a mere waste of time to attempt to teach the average adult Indian the ways of the white man. He can be tamed, and that is about all…our main hope lies with the youthful generations who are still measurably plastic.”

The similarities between Malidoma’s experience in West Africa and the experiences described in Education for Extinction are eerily similar:

- Malidoma was kidnapped. The same thing was happening here, so much that it had to become a law to stop it. “One thing that superintendents and Indian agents could not do after 1893 was send an Indian child to an off-reservation school without the ‘full consent’ of the child’s parents.”

- School wasn’t a gift. It was a war strategy.

- The same way Malidoma started off close to home then moved far away, the same thing here. “[Richard Henry] Pratt had called for locating off-reservation schools in fully civilized white communities, locations where Indian students might observe civilization in its most advanced state…and where the psychological pull of reservation life on students would be minimized.”

- The Trail of Tears took place between about 1830-1850, so boarding schools were in the days of reservations.

- Malidoma said “The worst thing is that [colonialism] uses the local people to enforce itself. Our teachers were Black, from the tribe, yet they were our worst enemies.” Education for Extinction pointed out that “Pratt took a particularly risky step when he decided that the white guards should be removed and an Indian company be organized to patrol the prison. The plan worked brilliantly…Fort Marion began to take on all the attributes of a military camp, with smart-looking officers barking out commands and carefully drilled soldiers marching in perfect timing.”

- Jails and prisons didn’t exist in Africa or North America before Europeans arrived.

- Malidoma said “The first year on the Mission Hill was thus dominated by an apprenticeship to the language of Father Maillot.” Education for Extinction pointed out that “The first priority was to provide the Indian child with the rudiments of an academic education, including the ability to read, write, and speak the English language.”

The last quote I want to share is from Education for Extinction about the second priority of the boarding schools: individualism. This one, I think, is the one that really got us out here flicked (a Black Savannah term for being “messed up”):

“Education would facilitate individualism in two ways. First, it should teach young Indians how to work. More specifically, it could teach them a host of practical skills and trades that would prepare them for the changed realities of their existence…But teaching Indians how to work was not enough. In the end, they must be inculcated with the values and beliefs of private property; they must internalize the ideal of self-reliance; and they must come to realize that the accumulation of personal wealth is a moral obligation.”

A few ways that we’re still helping colonization succeed:

- Defending respectability politics which basically say that we’re better off (we’ll survive and even succeed) if we talk right, dress right, and act right. And considering it “ignorant” when folk don’t subscribe.

- Calling Black English wrong, slang, backwards, not proper, etc.

- Believing that we can’t trust nobody and saying things like “I came into this world by myself and I’ll go out alone too.”

- Thinking that working more than resting is the answer to all your problems, especially if you believe in “rising and grinding” and “sleeping when you’re dead.”

- Feeling guilty for resting.

- Neglecting your health.

- Prioritizing money over everything, including saying “if it don’t make money, it don’t make sense.”

- Associating hoodoo and voodoo with evil.

- Pressuring our children to have their life plans figured out by 18.

- Refusing to give your children “black names” because you’re scared they won’t succeed in life.

- Thinking poverty just means having little/no money.

- Thinking you’re living better than your cousins in the country just because your way of life is faster.

- Not considering how you’re harming the Earth (especially if you don’t care that you’re harming Mama Earth).

- Buying what you can’t afford to be accepted/admired.

- Measuring your self-worth by how much money you have.

- Owning a business that can afford to pay livable wages but refuses to.

- Overworking employees to save money when the company can afford to do more hiring.

- Equating being “booked and busy” to being successful.

- Considering white museums, white restaurants, and vacations to Europe as being more “cultured” than black museums, black restaurants, or Africa.

Feel free to add to this list and to share your thoughts or what you’ve researched or heard from your elders.

If you like this post, you’ll love the book. Get yours. If you wanna Cashapp a dolla or two for all the love + time put into the research and writing, we thank you in advance: $KrakTeet