Zora’s Audacity is Why Krak Teet Exists

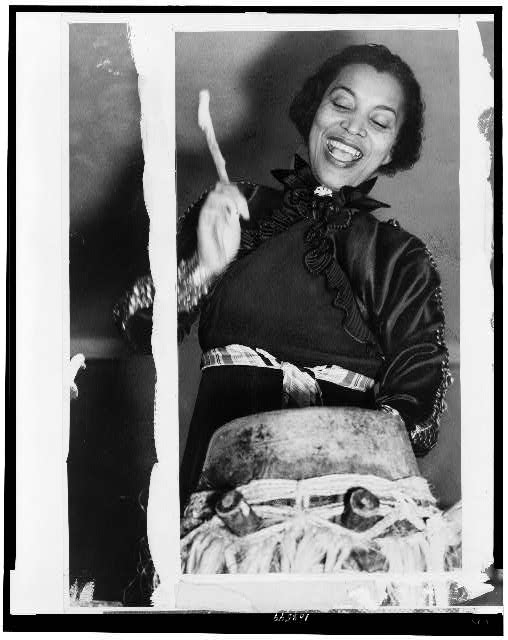

We celebrate Zora as an amazing author and anthropologist who gave us Their Eyes Were Watching God and Barracoon. We salute Eatonville, where she was raised for being one of the first all-black, self-governing towns in this country. We chuckle over the fact that she lied about her age for most of her life, and swoon over her being an integral part of the Harlem Renaissance.

But are we acknowledging the fullness of who she was? The extent of the role she embraced during the Harlem Renaissance?

The Harlem Renaissance was a celebration of the “New Negro.” The New Negro’s mama or grandfather were old negroes; they were born enslaved. But the New Negro was born free, had some money in their pocket, had style, class, talent, and there were no traces of slavery in the New Negro’s walk or talk.

Renaissance means “rebirth,” and the 1920s and ’30s was indeed a new day, a rebirth, for a lot of black folk who had moved to places like New Yawk. Breaking away from white folks’ stereotype about black people was something the New Negro took pride in. And if segregation was the case, then make the black side a place you wanna be.

The new opportunities and freedoms for black folk during that time gave artists a lot to explore. There was so much newness to express. And, like many black artists, Zora wrote about this new reality. There was still so much sameness, too, and Zora wrote about that as well.

In Their Eyes Were Watching God, Janie didn’t say “I came back home because nothing makes me happy where I was anymore.” She said, “Dat’s de only reason you see me back here–cause Ah ain’t got nothing to make me happy no more where Ah was at.”

One black writers called Zora’s characters “pseudo-primitives,” and he claimed she ignored how hard life was for black folk in the South. Never in the history of black folk anywhere, however, has our struggle overshadowed our existence. We live full lives, despite what white folks got us dealing with. Zora’s stories reflected black life outside of the white gaze.

As a writer, it can be tough to just write the story and not worry about how it’ll be received. It’s even harder to be given a hard time about how you write and still show up to page the next day to write some more. Zora did though, time and time again.

And I’m sure she read for research, but she also gassed up her car, Sassy Susie, and hit the road. She’d get on trains and boats, too, to go see for herself. When she got there, she wasn’t just the observer; she joined in. Textbooks call that “cultural immersion.”

She went to New Orleans to learn about hoodoo and become a practitioner and ended up naked on a coach, belly down on snakeskin, for three days without food or water. She believed that to write a story, you had to live it. I agree. To write a good story, I believe, you gotta be willing to put your opinions/ideas out there even when it ain’t supported. Zora would agree.

One of her most controversial pieces was called “Court Order Can’t Make Races Mix.” In it, she described the Brown vs Board ruling as insulting. She wrote, “I see no tragedy in being too dark to be invited to a white social affair.” At the end, she added, which I love and use, “Thems my sentiments and I am sticking by them.”

Seven years before she wrote that piece, she was falsely accused of molesting a boy. She wasn’t even in the country when it was said to have happened, so the case was dropped. It had already damaged her reputation though. I think this was the hardest season of her life. She even considered suicide. She got through it though, and you don’t bounce back from stuff like that the same. Above all else, you learn how to move on.

In her younger days, she married and divorced three times. So moving on wasn’t new to Zora. From girlhood ’til the day she died in 1960, her life was about moving on. Move on, re-invent yourself, and look forward to what’s next. In 1973, another one of my favorite writers, Alice Walker, had a tombstone built for Zora’s grave that rightfully reads, “A Genius of the South.”

I wanna make sure we celebrate Zora for all she was. A woman who didn’t let life just happen to her. She was intentional. She wanted to see the world and she saw it, and wrote about what she witnessed and experienced. She created what she thought was a good idea, even when others didn’t agree, and her audacity changed the game.

Her audacity is why Krak Teet exists.

P.S.: That first picture/painting is Najee Dorsey’s. Click here to read his thoughts on Zora‘s spirit and how he’s using his art to keep the Zora Neale Hurston Festival thriving.

If you like this post, you’ll love the book. Get yours. If you wanna Cashapp a dolla or two for all the love + time put into the research and writing, do so here: $TrelaniMichelle